Today’s digital learning technology allows instructors and learning designers to create highly-interactive lessons that can be used as in-class activities, as take-home assignments for flipped/blended courses, or as one module of a fully-online class.

With the right technology, active learning experiences can be scaled to hundreds or thousands of learners. They can also meet accessibility standards while still providing a good experience for learners with disabilities, surpassing the traditional classroom in the ability to support all learners.

It’s always important to note that some activities lend themselves well to interaction from any device — and some don’t. If you want to create active learning experiences that are equally wonderful experiences on desktop, tablet, and mobile, you must plan ahead and take into consideration the size, layout, and complexity of your activity.

According to Google Trends reporting, ‘active learning’ and ‘interactive learning’ have enjoyed a pretty steady following since 2004 (which is as far back as Google Trends data goes), with ‘active learning’ recently seeing a boosted interest. Other loosely-related terms such as ‘learning by doing’ and ‘project-based learning’ have been less popular in comparison, but still capture ongoing interest.

What do we think it means that ‘active learning’ has replaced ‘interactive learning’ as the frontrunner in our minds and Google searches? Perhaps interactive learning originally came alongside the question, “How do I get students to interact with my lesson?” which has been left behind as instructors learned that ‘just doing something’ is not good enough… whereas active learning is a recognized pedagogical practice with research-based underpinnings that showcase explain why it positively impacts student learning.

Active learning in the global market

In the 2017 Digital Learning Innovation Report, which surveyed university educators across Australia, the majority of instructors reported that they currently employ some type of active learning technology. That included discussion boards (75%) and tools specializing in interactive learning (65%). The interactive learning options outstripped more passive learning options, such as lecture capture (63%) and presentations (49%).

In the United States, the Department of Education created the National Education Technology Plan (NETP), a plan articulates a vision of equity, active use, and collaborative leadership to make everywhere, all-the-time learning possible. They also shared a Higher Education supplement to examine learning, teaching, leadership, assessment, and infrastructure in the context of higher education. About active learning, they shared:

Technology can provide instructors with the means of creating active learning environments that connect students with content in different ways… For example, rather than traditional lectures, instructors using these tools can create active learning environments that encourage students to collaborate, participate in inquiry based learning, and jointly produce content that demonstrates their learning. In addition, learning can be organized around real-world challenges and scenarios so students can master skills and work together to find collaborative solutions.

In recommendations for improving teaching practices through technology, the NETP report went on to say, "Instructors should use technology to reimagine courses in ways that more actively engage students, are more inclusive of different learning needs, and enable a collaborative and flexible learning environment."

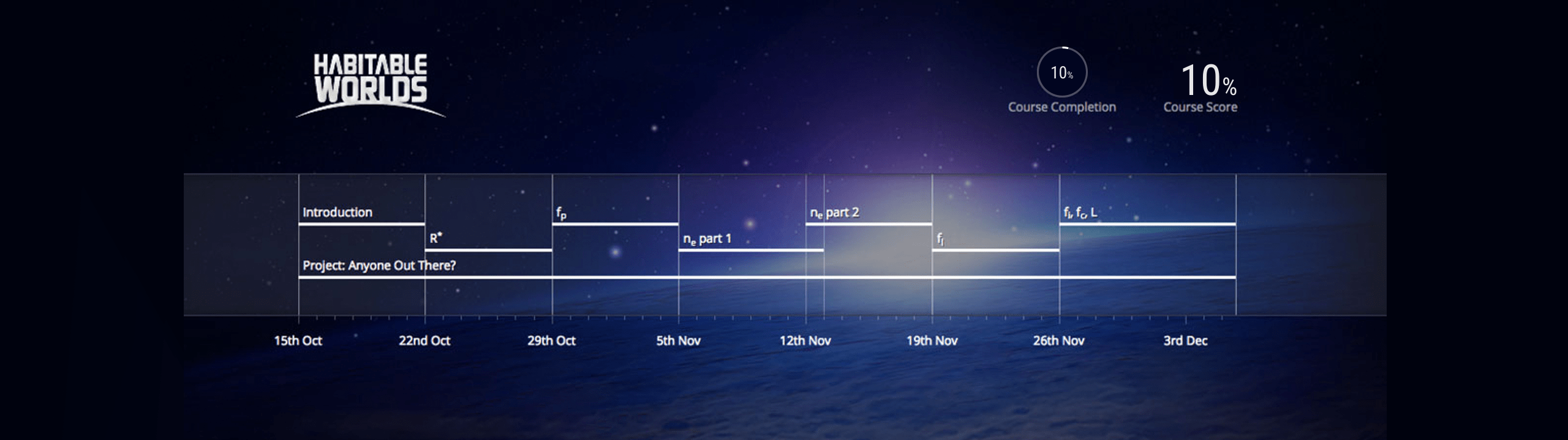

Example of a virtual field trip created by the California State University East Bay, to introduce new students to campus before they arrive. This is one of several explorable locations available in the online orientation courseware.

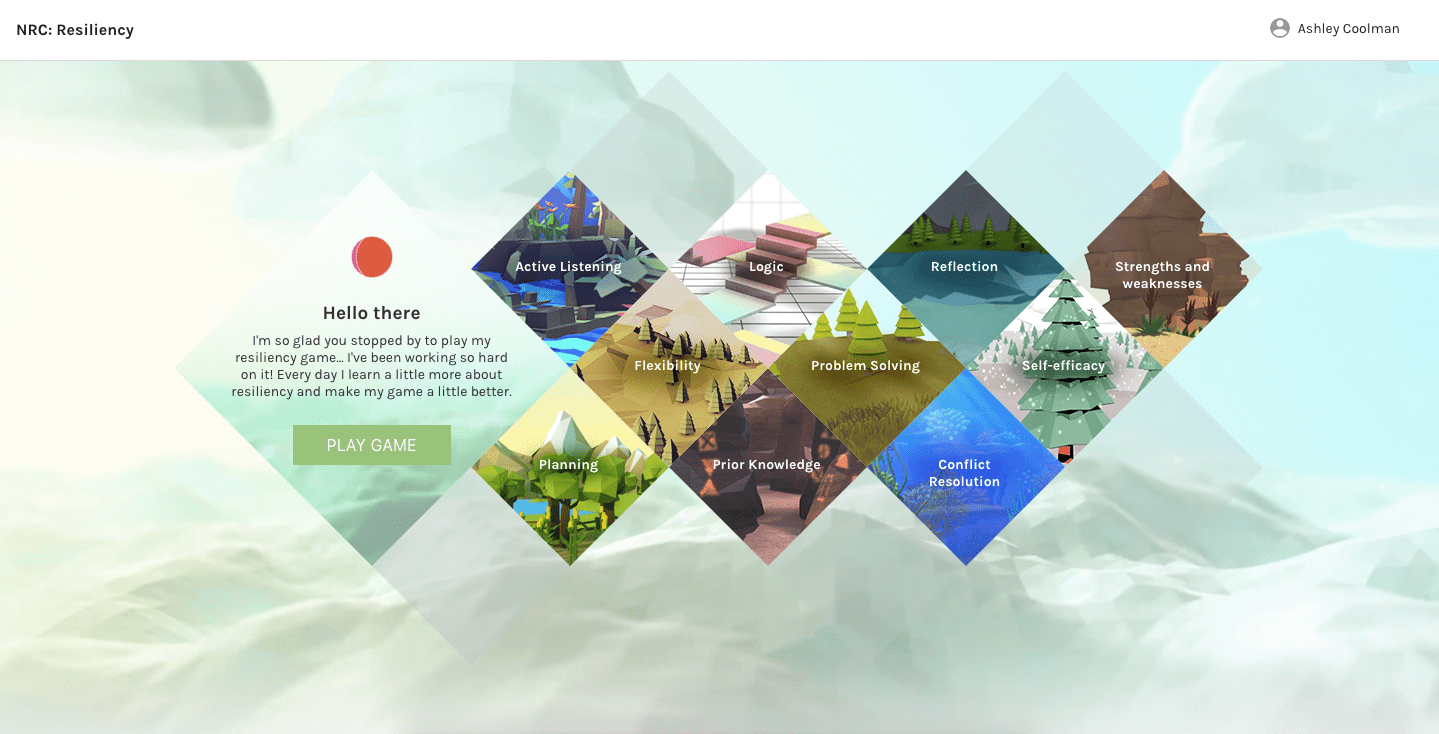

Example of a virtual field trip created by the California State University East Bay, to introduce new students to campus before they arrive. This is one of several explorable locations available in the online orientation courseware. Game "Dot resiliency series" courseware created by the Northest Resiliency Consortium (NRC), used to give learners insight into their mental state during challenge tasks.

Game "Dot resiliency series" courseware created by the Northest Resiliency Consortium (NRC), used to give learners insight into their mental state during challenge tasks.